When teaching writing in elementary and middle school, one of the challenges is how to keep moving forward with the different genre studies (narrative, expository and opinion … and don’t forget poetry!) while giving students the differentiated instruction that they need. At La Cosecha I learned of a way to do just that.

Using the units proposed by Lucy Calkins or the units created by your district (or by you) the first step is to begin each unit using a simple prompt that will let you complete a pre-assessment to find out what the students already know. You can assess their writing using the rubric to guide your instruction during the unit. My experience has been, though, that those first drafts show too many holes to be of much use; the students need instruction in many areas.

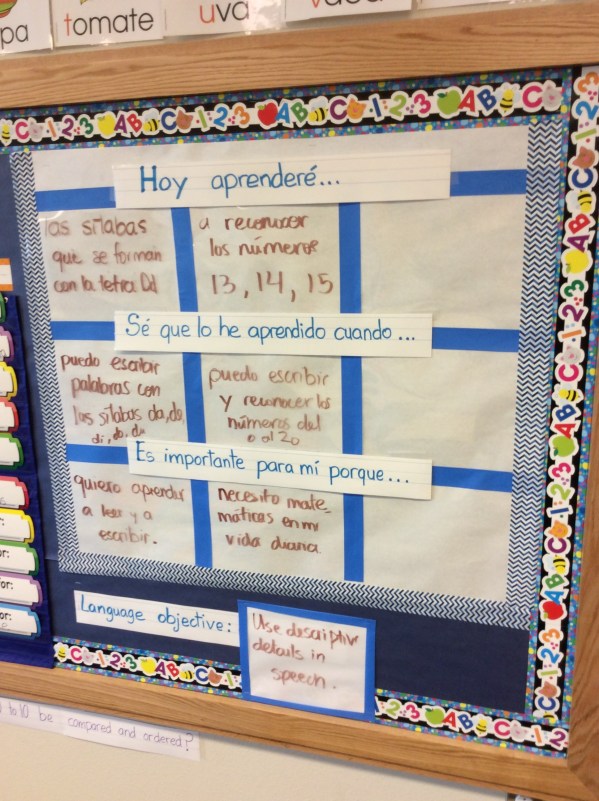

Then, after teaching the unit while referring often to the rubric and publishing a final draft, use the same prompt you used at the beginning of the unit. This time, it is important to use the rubric to deeply analyze the writing. The first thing you will most likely notice is a vast improvement over the initial use of the prompt. However, if you use the rubric and turn the information into numbers (see image to the right) you will see trends including areas that need specific attention.

Then, after teaching the unit while referring often to the rubric and publishing a final draft, use the same prompt you used at the beginning of the unit. This time, it is important to use the rubric to deeply analyze the writing. The first thing you will most likely notice is a vast improvement over the initial use of the prompt. However, if you use the rubric and turn the information into numbers (see image to the right) you will see trends including areas that need specific attention.

This is where the differentiation can happen. Based on the needs you notice, you can form groups of students for differentiated instruction just as you would do during reader’s workshop. This small group work could happen during the first week of the next unit or you could schedule a week in between each unit for the differentiated instruction. Use the CCSS to decide which areas are of greatest need. You might also decide that a change in tier 1 instruction would be most appropriate (e.g. focus on punctuation during morning meeting). You can let this assessment guide you during the next unit of study.

One more idea that I loved: sketch the story then touch and tell. Oral rehearsal!

Resources: Lucy Calkins: Writing Pathways, WIDA Writing Rubric

At

At